Interview with Director Silvio Soldini who received the Braille Award for his film Il colore nascosto delle cose.

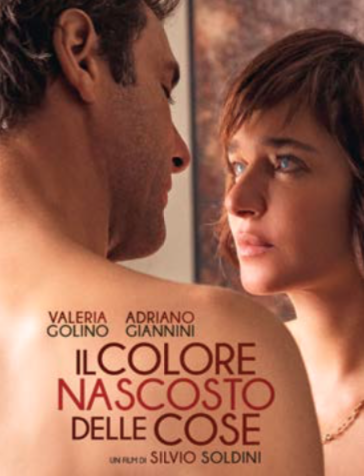

The looking glass-self theory in psychoanalysis is the idea that people serve as the mirrors that reflect images of ourselves since early childhood, creating a sense of self. If that is so, how does this translate for people living with vision loss? As often happens in the paradoxes of life, it is precisely a film director, a profession of storytelling through images, who has ventured into exploring the world of those who do not see. Silvio Soldini is an Italian director with a profound sensitivity. From his impressive filmography, he was awarded a David di Donatello for Bread and Tulips after winning the Nastro d'argento (Silver Ribbon) in 2014 with the documentary Per altri occhi - avventure quotidiane di un manipolo di ciechi (For other eyes - daily adventures of a handful of blinds). His movie Il colore nascosto delle cose (The hidden colour of things) was just released in cinemas. The film, starring Valeria Golino and Alessandro Giannini, tells the story of a blind woman, an osteopath, and of an ambitious publicist, exploring two ways of seeing and perceiving reality. And it is indeed the hidden colour of things that, often taken for granted or made invisible by appearances, the protagonist of the film will learn to really see.

Blindness does not imply a cognitive limitation, but a practical one. In a society that makes appearances the essential instrument of knowledge, what can those who do not see teach us?

Sight is definitely the sense to which we give the most importance, also because the world around us is built on appearances, on what we think we see. Visual information is plentiful, but perhaps truth may be revealed in more depth through the other senses. In fact, from the meetings I've had with blind people, I understood how they can immediately arrive at the truth of things to really understand who is there in front of them without forming an opinion based on sight, while we immediately pass judgment with a single look..

Blind people develop an unconventional vision of the world. Is there, perhaps, a point of contact with the director whose job it is to have an original vision of things?

Yes, while I was preparing the film, I was helped by blind and visually impaired friends and their advice was very important. In addition to telling screenwriters and me some anecdotes and peculiarities, they helped us understand if what we were writing was working or if there was something we needed to pay careful attention to. When we first read the script to them, I felt they had a very special ability to listen and concentrate. And while they were listening they were translating my words into a film they already saw, imagining scenes that I myself had not yet known how I would shoot. It is this ability that I tried to capture when, the first time the protagonist goes out with these two women, one who is blind and the other with a severe visual impairment, he is amazed to listen to them speaking about films and cities, the world they perceive without seeing it.

In the end, the motivation that drives each of us to go further is the same: passion, curiosity, desire for knowledge. How was it taken a step further in Il colore nascosto delle cose?

After my first appointment with my blind physiotherapist and the documentary Per altri occhi, I decided to learn more about this world, because I had not experienced through cinema a story close to reality. The image was very different, there was always a stereotypical point of view. I also tried to represent the joy, the irony, and the desire to celebrate life fully by those who do not see, telling how a person with a disability can teach things to so-called normal people. We live immersed in hurriedness and stress, and in the film the meeting with those who do not see is the motivation to slow down, to really go elsewhere, and it is when the protagonist goes beyond his conventionalism that he understands he can’t go back.

The Louis Braille Award you received recognizes in your film a commitment to increase social and cultural inclusion of blind and visually impaired people. There is still so much to be done to ensure that, as the poet says, one can really say, "I have no pity for any of you, I have only my eyes in yours."

We must finally tear down the wall that separates us from otherness in general. Because of what may be different in a person with a disability, we have difficulty relating to them, we are hesitant to approach them, or we experience feelings of sympathy. I think that the more we’ll succeed in breaking down these barriers and the more there will be an exchange of mutual enrichment. I hope this film can be instrumental in that way.

.png)