In honour of the five hundred years since the death of Raffello Sanzio, we present the Ecstasy of Santa Cecilia, a masterpiece by Urbinate, painted on wood and transported on canvas, whose date goes back to 1513 or 1514, even if a rereading of the documents and historical sources leads to a post-dating referable to 1517 or 1518. The work, of great dimensions, has been the object of study and extensive scientific literature since the sixteenth century. Its fame is attributed as much to its iconographic peculiarity as to its pictorial quality, the result of an artistic maturity and a classical essence of Raphaelesque painting. In order to decipher the cultured and self-righteous conception of Renaissance iconography, it is necessary to develop a synthesis of perfectly integrated philosophical and religious elements, aimed at an ethical teaching never deprived of the dialectical relationship between the mysticism of the medieval culture and the rise of humanistic thought in liberal arts. The same scope of meaning of the symbolic and iconic representation of Saint Cecilia, virgin, martyr, and patroness of celestial and terrestrial music, should prompt us to reflect, internalize and assimilate the idea of the coexistence of human and sacred characters inherent in Christian doctrine and in the practice of her own iconic representation. The first theorist who spoke out on the work was Giorgio Vasari, who in 1550 determined the occasion of the commission, the role of Cardinal Lorenzo Pucci and the destination we know, at the Duglioli-Bentivoglio Chapel of the Church of San Giovanni in Monte, in Bologna.

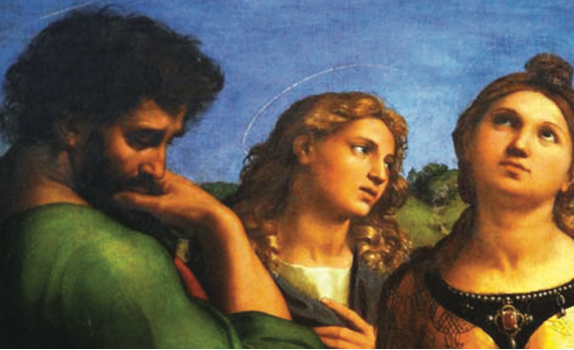

In his works, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, he also distinguished the autography, attributing the performance of musical instruments to Giovanni da Udine who, for style and workmanship, "[...] made his painting so similar to that of Raphael, which seems to be of the same hand [...]." Vasari wrote about the famous episode of the astonishment, and the legendary "beautiful Death" of Francesco Raibolini, called Francia, who in seeing such incomparable beauty felt that Raphael's work was not painted but alive, and so well coloured by him [...] hence Francia almost died of terror, the beauty of the painting that such [...] in a few days' time he was bedridden, feeling pain and melancholy, close to death [...]." Raphael's painting is a metaphor with the Sacred: Cecilia gives herself to her god through a privileged and inner relationship with the harmonia mundi. Against the background of dense clouds, she, in the centre of the composition, surrenders herself to the contemplation of the celestial chorus that overlooks from a glimmer of light, intoning the harmony of the spheres. Her gaze, turned to heaven, distracts us from the earthly dimension where are immersed the four Saints identified with Paul and John the Evangelist, placed to the right of Cecilia, and Augustine and Magdalene, placed to her left.

The Saints do not participate in the ecstasy of the virgin martyr because they cannot see, nor hear, what is perceived only by Cecilia. It seems almost as if the saint is sliding the portable organ from her hands, whose pipes, upside down, are partly detaching from the chest. The instrument, which has become her attribute for a singular interpretation of the Passio Sanctae Caeciliae, appears silent in the hands of the girl, leaning towards the intimate listening of metaphysical polyphonies. At Cecilia's feet lie musical instruments symbolically shattered, and therefore unusable. They represent the finiteness of earthly music compared to divine music. A viol has broken strings, the flutes scattered on the ground are also broken, between a triangle and a bell collar. Finally, a tambourine, cymbals and some eardrums with broken membranes evoke the sounds of glory and deceptive worldly seductions. If from an iconographic point of view the choice of instruments dominates the work, from an iconological point of view, the extension of the sense of iconography, it is precisely the mystical inspiration combined with the Raphaelesque solemnity, borrowed from the greatness of classical models, that makes the doctrinal message of this painting unequivocal and at the same time a source of inexhaustible enchantment. The Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia is also a symbol of the human being's unceasing struggle towards an unattainable otherness, and of a loneliness that brings him closer to the supernatural through a dismissal from the mundane.

Saint Paul, in the solid posture of the figure portrayed, meditates on broken harmony, thus on vanitas and hence on the fragility of human things. St. John the Evangelist, with his traditionally ephebic and delicate features, carries his left hand to his heart and with his reclining head he stands next to Cecilia. St. Augustine, facing John, is represented in profile, a vigilant and austere presence, while Magdalene, with her gaze towards the observer, seems to welcome the faithful within the scene to guide them on a path of theological reading and understanding. At the National Gallery of Bologna, where the masterpiece is kept and exhibited, through the training courses organized by the Anteros Tactile Museum, it is possible to learn about relief drawings dedicated to visually impaired people, to make this famous pictorial composition readable, to the touch. With the support of proprioceptive and kinesthetic experiences, the vision of a tableau vivant is born spontaneously.

.png)