On June 19, 2021, in the column that Professor Umberto Galimberti writes in Annex D of the newspaper la Repubblica, a reader asked the philosopher why the Stendhal syndrome – a phenomenon described by the French writer in his 1817 book Rome, Naples, Florence (published by Bompiani) and associated with the vision of a painting – “has never been described for listening to a piece of music.” With his usual precision, Galimberti, beginning with the description of the syndrome by Stendhal and “characterized by tachycardia, dizziness, lightheadedness, mental confusion that had afflicted him in the presence of works of art,” expanded on the citation of the thought of great philosophers and writers and reported the hypothesis of neuroscience about mirror neurons, which could activate in the observer “the same emotional states [....] of the author of the work of art.” He attributed the same characteristics and dignity of works of art to music, “which does not exhaust its meaning in what is heard but refers to that which is unspeakable to what music relates to.” Finally, the professor concluded his reply by speaking of the “presence of the disquieting which, as a typical trait of beauty, is revealed in every work of art. And only those who don’t have eyes for beauty don’t sense it.”

I confess that I felt a strong sense of loss, as if the ground beneath my feet was disappearing. I could not help but feel like a part, albeit small, of these phenomena. My memory went to grasp the depths of my experience, but, at the same time, I was comforted by the existence of a present that has never ceased to bear witness to the persistence of sensations and awareness called to mind by that reading. It is of myself that I ultimately try to speak, though I am not certain that my subjective experiences and perceptions can be associated with the Stendhal syndrome. As it may be, on the one hand, I was led back to the 1974-1975 opera season of Bologna’s Community Theatre. On the other hand, I am trying to relate the experience of listening to a specific piece of music. In the first instance, I was faced with my initial encounter with Le Nozze di Figaro by Mozart, a musician I have loved since childhood. At the premiere of the opera, I was seated in a box on the top tier and adjacent to the stage. I was a guest of some friends from the Istituto Cavazza in Bologna, where I used to work. It was nearly impossible to see what was happening on the stage. I was leaning over the parapet in vain for almost the entire evening, bracing myself with my arms in an uncomfortable position. By the end, I was exhausted but moved and ready to repeat the experience immediately. I remember hugging with enthusiasm the people who were with me, thanking them for their gift to me. During that season and the following one, I attended, sitting in different parts of the theatre, about ten performances of Mozart’s masterpiece, increasingly fascinated by the psychological “truth” of that musical comedy.

In one circumstance, and for a time that I cannot possibly measure, I realized that I was no longer hearing the music. Everything was so real and connected that I had the distinct feeling that I was watching a representation of the theatre season, in which the miracle of a perfect merge of different (but equal) elements was taking place. If I may say, it had something to do with consubstantiality. I will never forget this, and I cannot help but think that these conditions are unrepeatable. The trivial stage directions and sets of our days, which falsify history by turning everything to the present, make any potential achievement of such spiritual unity unattainable.

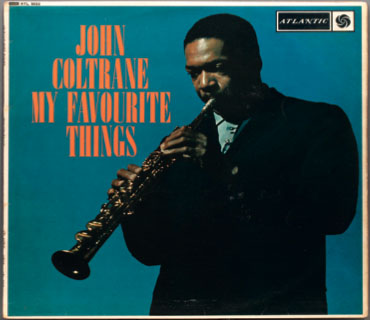

The second reality I would like to address is about an entirely different genre of music. The nature of this music – jazz – with its unique and unforgettable experiences could make what I am about to write appear contradictory. The possibility of capturing through an album any musical experience would be vain and useless if it did not have the capability to make it irreplaceable, essential, unique, desirable as a love, ready to repeat itself in different ways. The musician who has reached this peak–I am sure of it, a conscious promoter of this extraordinary phenomenon–is John Coltrane with one of his forty-five immortalized interpretations on record of a popular waltz by Rodgers and Hammerstein, My Favorite Things. Only one of them, however, captured me so powerfully: his interpretation at the Newport Festival in 1963. I am not a musician, even if I have some knowledge on the subject having made very distant, partial, and badly accomplished piano studies. But it is not necessary to have theoretical notions to be overwhelmed to the point of trembling because of an incessant whirlwind in which you feel you are in front of an event in which total command and technical mastery are constantly and fully put at the service of an emotional challenge that is difficult to express in words. Here again two elements come together in a winning creative form never previously touched upon and no longer performed with Coltrane’s adherence to the language of free jazz in the last years of his life. That music gives you no respite, leaves you no escape, prevents you from denying that there is hope of happiness, of a devastating but beneficial and regenerating force. The musician touches this climax here thanks also to the lightning-fast tempo never before adopted. You are immediately hit by an avalanche that takes your breath away, but you manage to control and follow through. Obviously, it is The Musician who is wrapped in that grip, but you end up blending in with him. There is a precise point at which the saxophonist is so heavily immersed in the creative trance that, if he had not kept it under control and dared to go beyond it by even a notch, he would probably have choked to death.

The then director of the magazine Musica Jazz, the lawyer Arrigo Polillo, reviewing that posthumous record said that that music could only be endured. Looking back now on that enthusiastic judgment, from which it was inferred that he himself had emerged from such an experience stunned, I cannot agree with him. In fact, every time I listen to that My Favorite Things I feel an integral part with it, I relive it as if it were me playing it, I feel that momentum and vigour are the result of a utopian (I would be ready to use the term “heroism”) but beneficial force that defies the impossibility of exhausting the totality of combinations and variations in music. In my opinion, and to my knowledge, this is the most unstoppable hurricane in the history of Music. If I really have to make a comparison, I can only go back to fifty years earlier, when Igor Stravinsky–with a totally different piece of music–shocked the twentieth century with Le Sacre du Printemps. Perhaps the definition of “short century,” applied to the twentieth century, also finds its justified fulfilment in this case. I remember, with emotion and pride, that I introduced that record to one of the youths who were at the theatre for the premiere of Mozart’s opera and that I saw that same incredulous emotion etched on his face.

.png)