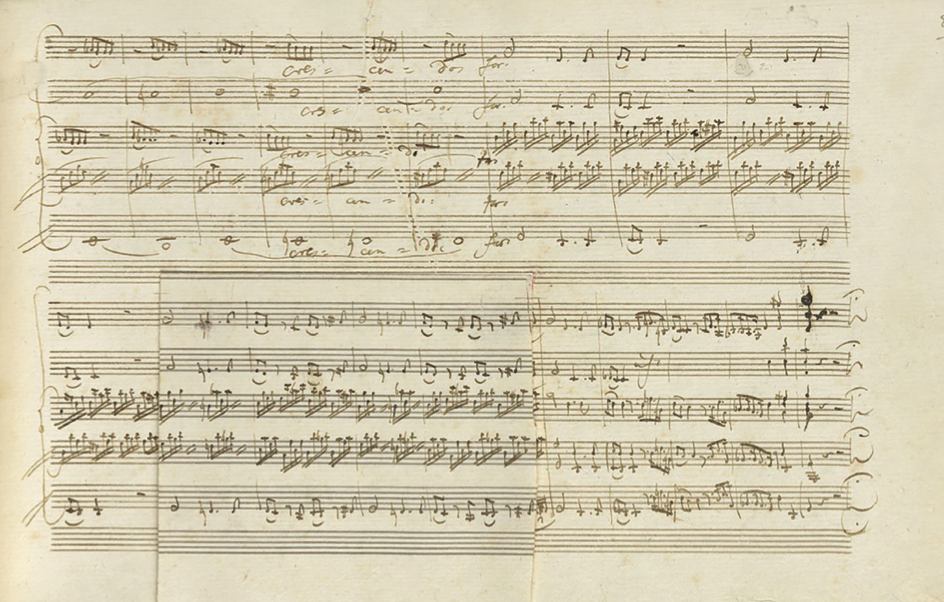

Mozart, in other words, the inability to be normal. This stigma, common to all the great geniuses of history, means for Mozart an existential chaos that precludes any possibility of leading a stable social life. Perhaps we should understand the meaning of the word “normal,” with the risk, however, of abandoning the musical sphere to embrace the psychoanalytical one. The cover of the 2nd CD of the chamber music group Il Tetraone immediately clarifies the interpretative journey that guided the four musicians in the execution of the quartets for pianoforte and strings K 478 and K 493. The words: a real profession of intent and not just a pure play on words, in homage to the musician’s frenzied need to express himself through jokes and obscenities that came out naturally, without any particular ostentation. This is also the result of a family environment that seems to have abandoned itself to such expressive modes without any problems, in compliance with the Salzburg social milieu of the time. The gesture of defiance by Mozart against the despised archbishop of Salzburg, Hyeronimus Colloredo, cost him, in 1781, the humiliation of a stomp in the butt by Count Arco who, in this way, expressed his disapproval. At the same time, the impossibility of denying his own creativity, caused the musician in 1785 to break the agreement signed with the Viennese publisher and friend Hoffmeister for the composition of three quartets, of which only the first had been completed, the K 478. Too complex to be understood and accepted by the Viennese public that, at that time, was only seeking confirmation, that is music of immediate fruition, while Mozart was exploring new paths in the pure chamber music realm. There is none of the gallant spirit with which Bach’s two sons Johann Christian and Carl Philipp Emanuel would probably have treated pieces composed for the same ensemble. Mozart goes beyond that; he is not interested in pleasing and complacency. Fortunately for us, it is to himself that he is accountable, and he had to stay true to himself. How should we say: to read Mozart you have to write Trazom. A genuine admonition, an invitation to reconsider the figure of the musician, mysterious as few. Investigated, studied endlessly, practically from the moment of his death and with an unstoppable crescendo until 1991, the bicentenary of his death, Mozart has been interpreted and played by legions of musicians, the areas in which he expressed himself being boundless. Yet, one still has the feeling that Salzburg remains unapproachable, unattainable, an unkept promise, an unfulfilled goal whose expressive and interpretative potential is far from being fully explored, and this in spite of the apparent ease and immediacy of his music. Rereading Mozart upside down does not mean distorting him, but, if anything, investigating him, trying to understand if and to what extent we should disregard the endless interpretative production mentioned above. And this in order to find the image of an essential musician, around which classicism and the imminent romanticism revolve, to get closer to an interpretation that is certainly not definitive, but, at least, reliable, if it ever existed.

L’interpretazione del Tetraone è interlocutoria. Il gruppo va in profondità, scava, si prende i suoi tempi, dilatati, ariosi, quasi a domandarsi come possa eseguire quella musica, quale sia il possibile e corretto accostamento a Mozart. E per questo i componenti del quartetto esitano, si soffermano: si avverte in loro come una forma di pudore, un entrare in punta di piedi in un mondo che è stato scandagliato da legioni di esecutori, ma che ancora non sembra(va) aver visto messi in luce tutti i meandri nascosti, posta in evidenza la luce stessa insita in quelle (come in tantissime altre) composizioni mozartiane. Quasi confessino di non sapere se siano in grado di assolvere quel compito e a chiedersi timorosi se il loro approccio non sia che “uno fra i tanti”. Se cauto appare l’avvicinamento, nel timore di non riuscire a cogliere la visione interpretativa ideale, di non accorgersi della potenzialità ultima di un’idea interpretativa, il contrario avviene con la sicura padronanza del suono degli strumenti. Le pur minime perplessità sollevate dall’esecuzione del primo CD del Tetraone – come le lievissime asperità del violino che avrebbero potuto alterare gli equilibri interni al gruppo e bloccare lo slancio interpretativo – scompaiono del tutto nelle esecuzioni mozartiane. Il suono è fluido, sicuro, ma al tempo stesso controllato. Il fortepiano, il violino, la viola e il violoncello si fondono in un’unità compiuta, in cui non si avverte la minima prevaricazione dell’uno sugli altri, ma, al tempo stesso, le linee sonore dei quattro strumenti antichi sono chiaramente distinguibili senza alcuna fatica. Dell’insieme di questi dati si giova soprattutto il quartetto in sol minore, ricco di silenzi e di momenti forse inespressi nella partitura, quasi a voler lasciare agli esecutori il compito di trovarli.Queste due esecuzioni si calano all’interno di un Mozart che forse presagisce se stesso e che, pur essendo già nel pieno della sua maturità, si proietta nei grandi ulteriori capolavori che creerà nei 5/6 anni che gli restano da vivere. La chiave interpretativa utilizzata dal Tetraone per il quartetto K 478 potrebbe seguire e presagire i seguenti due mondi: Mozart aveva da poco composte la fantasia K 475 e la sonata in do minore K 457 per pianoforte, il Concerto K 466, la Maurerische Trauermusik. Ma già poteva pensare al Quintetto per archi in sol minore K 516, forse anche al Don Giovanni, se ascoltiamo le battute finali dell’opera, in cui – nell’interpretazione di alcuni geniali direttori - la musica quasi si ferma in un’impercettibile esitazione, subito prima della conferma finale in cui il sipario si chiude definitivamente su quella simbolica vicenda. Oppure a un brano intimo, di piccole dimensioni, quale l’adagio in si minore per pianoforte K 540.

The interpretation of the Tetraon is interlocutory. The group reaches deep, digs in, takes its time, dilated, airy, almost wondering how it can perform that music, what is the possible and correct approach to Mozart. And because of that, the quartet members hesitate, they pause: one senses in them a form of modesty, a tiptoeing into a world that has been plumbed by legions of performers, but that still does not seem to have seen all its hidden intricacies brought to light, to have highlighted the light itself inherent in those (as in so many other) Mozart compositions. They almost confess that they don’t know if they are capable of fulfilling the task and fearfully wonder if their approach is but “one among many.” If the approach appears cautious, in the fear of not being able to grasp the ideal interpretative vision, of not realizing the ultimate potentiality of an interpretative idea, the opposite happens with the confident mastery of the sound of the instruments. The minimal perplexities raised by the performance of the first CD of the Tetraone - such as the very slight asperities of the violin that could have altered the internal balance of the group and blocked the interpretative momentum - completely disappear in the Mozart performances. The sound is smooth, confident, yet controlled. The pianoforte, the violin, the viola, and the cello merge into an accomplished unity, in which there is not the slightest sense of dominance of one over the others, but, at the same time, the sound lines of the four classical instruments are clearly distinguishable without any effort. The Quartet in G minor is rich in silences and moments perhaps unexpressed in the score, as if to leave the performers the task of finding them. These two performances take place within a Mozart who is perhaps foreshadowing himself and who, while already in the prime of his maturity, is projecting himself into the great masterpieces he will create in the remaining five to six years of his life. The interpretive key used by the Tetraone for the Quartet K 478 could follow and foreshadow the following two worlds: Mozart had recently composed the fantasia K 475 and the C minor sonata K 457 for piano, the Concerto K 466, and the Maurerische Trauermusik. But he could already have been thinking of the quintet for strings in G minor K 516, perhaps even of Don Giovanni, if we listen to the final bars of the opera, in which - in the interpretation of some brilliant conductors - the music almost pauses in an imperceptible hesitation, just before the final confirmation in which the curtain closes definitively on that symbolic event. Or to an intimate, smaller piece such as the B minor adagio for piano K 540. If we go, more specifically, to the Quartet in E-flat K 493 - more airy, light, and delicate than the previous one - the world that surrounds it is that of the Nozze di Figaro, of the horn concertos, of those for piano and orchestra K 482 and K 488 and, perhaps, of the one immediately following. The concerto K 491, in fact, written in the relative minor key of the Quartet K 493, carries within itself the expression of a more intimate and less disruptive tragic nature than K 466, in D minor, written the previous year. Not to be forgotten, then, is the Trio dei Birilli, K 498, which is implicitly referred to on the CD cover: in it appears a large, ruined room which, if it weren’t for the door on the right in the background that opens onto a garden, might make us think of the former convent of San Francesco in Bagnacavallo, which hosts frequent musical performances. It also shows an old soccer table, perhaps as a reminder of Mozart’s passion for billiards.

An abbreviated version of the first movement of the Quartet K 478, with harpsichord instead of the pianoforte, completes the CD. Even though the new instrument was becoming popular in those years, it is presumable that in private homes it was much easier to find a harpsichord. It is therefore likely that, in the domestic sphere, Mozart’s keyboard music was performed on the old instrument. This is equivalent to saying that most of the musician’s contemporaries might never have suspected who Mozart really was, such is the difference in sonority, breath and expressiveness of the two instruments. Perhaps this was also the motivation for the inclusion of this final piece. Perhaps a last-minute decision since the CD case does not take this into account when indicating the total duration. An apt didactic motivation, but also a coup de théâtre. Compared to the previous CD, which contained Beethoven’s Quartet op. 16 and Schubert’s La Trota Quintet, there is a more intimate approach of the performers to the interpreted compositions. There is a more stringent unity factor, certainly fostered by the fact that one can and does dedicate oneself to a single musician, however, multifaceted qualitatively, but spiritually always true to oneself. Perhaps more freely, but at the same time aware of venturing into treacherous territory, for all the reasons already stated. The fact that the group, founded in 2011, has produced, in ten years, only two recordings is a guarantee of the commitment to deepening and studying the musical subject matter. The recording of the CD, which took place between the 5th and the 8th of October 2020 in the Church of San Girolamo in Bagnacavallo, had been preceded, a few days before, by a performance open to the public, which showed the Tetraone musicians careful listening and sincere applause.

.png)