Something

happened to me when I arrived at the office, a day on which I probably had

less appointments than usual, I took a few minutes to look around me and

realized that there was something strange. My colleagues, instead of

speaking on the phone, were "looking at it"! SMS, I thought, the flavour

of the moment, but I had a feeling of déjà vu. I had already been there

many years ago, entering the office and looking at my colleagues who

stopped writing on the keyboard to look at a cursor led by the mouse. They

were then the first icons of graphical operating systems and today? They

are the physical icons of domotic and environmental systems. In the 90s,

when reading a video file was tiresome, the user could select the icon

with the mouse and drag it on the printer icon and there it was.

Today,

with a iPhone, Android or Microsoft Surface, when it is inconvenient to

read the email from the phone, you just rest it on the printer and there

you go! But the mouse is no more; it is my hand doing the work instead.

The desktop is no longer the one on the video made of pixels and bits, but

they are the atoms of my real desk. If I want to share a photo with a

colleague, I lay the PDA on it and the picture immediately comes out of

the phone and opens on the desk. It can be widened and moved around with

the hands, the fingers of the user now replacing the mouse clicks or the

keyboard keys.

It is no longer the screen reader that guides me on the screen, it is rather a wireless system that follows me, that realizes that I am getting close to the elevator and, when I get in, reserves the floor where my desk's physical icon is or that of my colleague whose address book item on the mobile phone I have opened.

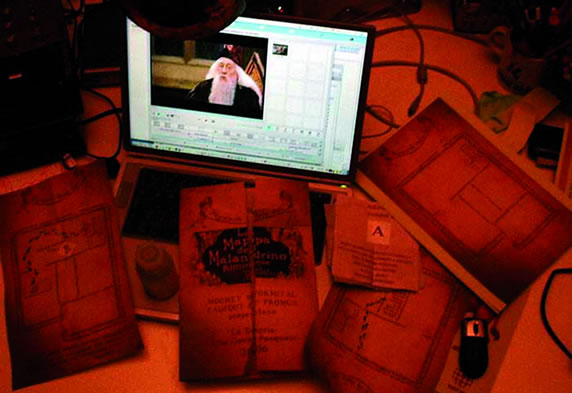

The PDA is like a real Harry Potter's “Marauder's Map" where instead of the representations of the places and objects of Hogwarts, the moves of Albus Silente, of Hermione Granger and professor McGranitt, here are my colleagues, the meeting hall, the queue at the coffee machine or at the cafeteria.

A new magic accomplished by mobile localization, tracing, guiding devices, by optical light, optical character recognition with which a blind person can find a yogurt cup, read what flavour it is and its expiration date, discover the colour of a vest, or photograph and read an image document that a colleague has opened on the desk. But the aids of the world of physical icons have not yet reached screen readers' efficiency for the blind when moving around on the desktop between graphical icons. They are growing fast however and they are doing it with an extra gear: the community of digital aid and open source. But the aids are not sufficient, from the information society (the world on the desk through the Internet) physical icons are guiding us towards the society of knowledge in which what counts is the sharing of one's own experience. From the global village, in which from my office I could read newspapers from New York or Sydney, with Web 2.0 we are turning to the

This entails a necessary transformation of the blind person: from being expert of assistive technology, he has to become expert of things close to his real life, that of his friends and colleagues.

Moreover, they have to change organizations putting more emphasis on integration than on independence. Physical icons are not what is inaccessible to the blind, but schools, universities or master's programs where groups are formed. The myth of independence, very important during the learning process of a person with disabilities, in daily or professional life is an autarchy, a "cape of invisibility" which relegates the blind person to his desk with the computer's desktop or the screen reader. If we help the blind person to free himself of the cap, we take him away for a few hours a day from the global village to bring him back to his own routine. Today more digital and technological then yesterday, it is true, it has a few more bits and a few less atoms, but certainly less virtual and more real, fun and moving than the Internet.

Mobile Wireless Accessibility, the project on which I have been working since 2004 with IBM, Asphi, Nokia and Cisco is exactly that. Technology, the best that the market offers for the interaction of persons with disabilities with the physical icons of an office or the business working groups, but most of all training, training and still training on the strategic activity of the professional world.