Opening a museum is an important milestone in the life of an institution. First of all, it is a matter of gathering a number of objects recovered from the past and giving them a conceptual form, even before some sort of order.

Museums are always made of objects, but what sets apart a museum from another is the story that is being told within.

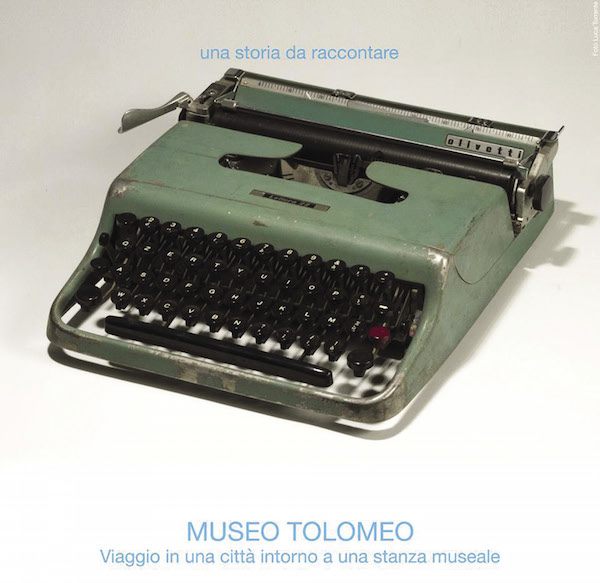

Here is the particular story of an institution that has long ago opened its doors to the city, but that has not yet presented itself as an instrument allowing us to see the city we experience from other perspectives. The history of which we speak is a story that is experienced by almost everyone today: the fact of leaving behind paper as the only support tool for communicating our ideas.

The issue of the paper form and the intangible medium has been in recent times on the agenda of various human communities. At the Institute for the Blind, this matter has been resolved for thirty years now: the print library lives in the cellars and in its place are not cold technologies, but a constant research on the subjects of reading and writing, which has made Cavazza a world leading centre in the experimentation of new languages.

The core of the story taking place in the museum on the subjects of reading and writing is an appropriate meeting with our contemporary world. It is said that we are a society that reads books less and less. It is certainly the time in which writing and reading are the two main activities of human communication, thanks to new technologies which exist through the act of writing and are fed content with short messages while we are in constant movement.

The museum, in its main goal of becoming a place where to learn about the history of the Institution, presents itself to the city with this first hall, a combination of period room and Wunderkammer: a place built around the living room of Count Cavazza, where is exhibited a collection of objects used in the Institute throughout more than a century of activities.

Building the collection during the months preceding the opening, hidden in the historical events of the Institute, as well as in its cellars ‒ bringing light to history ‒ is a story made of chronicles of single individuals, each with their own tale, their own experience becoming the expression of a more important story: the history of the Institute and that of Bologna. The museum is only a first step in this quest. It begins with the theme of the collection itself and reaches the end through a path of awareness and rediscovery about how, over the years, as part of the various activities held by the Institute within and outside its walls, the basic guideline of the Institute has been as follows: that of not providing a “sterile” assistance to so-called disadvantaged people, but on the contrary empowering them and giving them a sense of freedom and independence. A freedom gained through the instrument of culture and knowledge: from writing and reading, through music, to a solid research that, over the years, has allowed a steady development of high technology devices.

One last question: the name of the Museum.

The name is like a puzzle. It contains a word that is to be illuminated in some manner; by doing so, one will understand the meaning of the museum.

The name of Tolomeo has been for several centuries a synonym for something that no longer worked, an explanation of the universe that had no longer any reason to be.

The paradigm of Tolomeo does not have today a value linked to the cosmos; it is tied to the very idea of geography as to how we experience it in today's world.

In allowing us to see various aspects of the world, the portable technologies that we carry around have brought back the matter of the point of view at the centre of the debate.

The digital network is Cartesian, but it is populated and finds its value in presenting the multitude of points of view.

Each of us has become a centre through which to observe the world for others. Tolomeo is therefore a new metaphor through which to explain this new idea of the importance of the "point of view", of the position from which one looks, to explain how we define the world.

To tell the city what happened within its walls, showing how the relationship with the written word has been experienced in recent decades, exhibiting the aids intended as elements that work on the imagination is, as a whole, the proposition of one’s viewpoint of the Istituto Cavazza.

.png)